Unfortunately for all the European jingoists out there, this year's Giro D'Italia was dominated by Colombia. The top two podium spots were taken by Nairo Quintana and Rogoberto Uran. The mountains classification was another display of Colombian talent, with Julian Arredondo coming in first, Quintana third, and Jarlinson Pantano ninth. The young rider classification was more of the same-Quintana first, Sebastian Henao fifth.

Let me tell you why a country like Italy, whose terrain is 70% mountainous, can't produce any climbers-drugs. Aside from whatever Miguel Indurain was doing in Spain, it was the Italians first and foremost who embarked on a hardcore EPO regimen. As a country, THEY were the ones who introduced it, they were the ones who abused it the most, and their doctors, specifically Dr. Conconi, Dr. Ferrari, and Dr. Cecchini, were the prime movers of EPO administration in the pro peloton. This trickled down to the amateur ranks, where tales of 16 year-old riders already being put on heavy doses of EPO and other drugs have been rampant for years. During the late 90's early 2000's, the Italian junior ranks, according to an old report from Cycle Sport magazine, saw a collective increase in hematocrit levels that would have made Richard Virenque blush. This would have raised eyebrows anywhere else, but not in Italy.

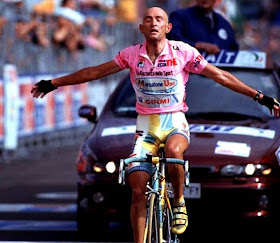

A respected member of the "Busting Chops" home office and one of the founding fathers of this blog said it best-"After a certain point, the amount of drugs you must take to ride stop working". If the top Italian juniors for the last 20-plus years have been saturating themselves with PED's, it's no wonder their collective performances start to level off and fizzle away when they become pros. Reading "The Death of Marco Pantani" by Matt Rendell, it was patently obvious that Marco rarely, if ever, rode without drugs. Despite his romantic aura, which was in direct contrast to Armstrong's corporate mercenary appeal, and his legion of diehard fans, he was just as much a product of drugs as Lance was. He may have had more natural talent to ride hills, but the truth is still the truth. The sad fact is, that despite turgid arguments over level playing fields among dopers, doping still conveyed undue strengths to riders who never possessed them in the first place.

Flawed hero Marco Pantani in better days-

Colombia is a land of high mountains and even higher altitude. This makes for the perfect breeding ground for climbers, and historically this has been the case. But only recently has there been breakout of young stars who can compete for three week grand tours. Time trials have always been the bane of climbers of any nationality, where a dedicated climber can lose upwards of four minutes in a flat time trial, negating any advantage they might hope to gain in the mountains. This is why it was a great move for team management to have Quintana ride the Giro instead of the Tour. The Tour this year had too many flat time trial miles to make anything but the King of the Mountains jersey and a top-three finish a realistic goal. A win in a grand tour for any European team is worth its weight in gold, even though in order of impact and importance the Giro sits second between the French Tour and the Spanish Vuelta. The Giro itself is mythic, and its climbs harder than those in France, though this is negated by the better quality fields of the French Tour to a degree.

Nairo Quintana comes from a small town that sits at 9,000 meters in altitude in Colombia, and rode a bike as a youth to get to and from school. He was climbing the second he began riding. A young man winning a grand tour at the age of 24 is auspicious enough, but of course, thanks to Lance Armstrong and others, there are those who believe EVERYONE in the peloton is on drugs. There hasn't been a hint that Quintana has ever doped, but don't tell that to his detractors. It's unfortunate that Quintana and other Colombian riders have to ride in an era where there are no grand tour riders with any talent or panache, but that is not their fault. These cycling fans are left cheering the likes of Cadel Evans, who is running on the exhaust fumes of a hearse, Vincenzo Nibali, who is the second coming of Ivan Basso (an impotent-legged bum who can't ride without dope) and other assorted nobodies like the Schleck brothers, who are so beyond their sell-by date they are beginning to reek of sour milk.

That's what I'm talking about-

Nairo Quintana representing his country at the 2013 Road Championships-

There is no one left except Alberto Contador and Chris Froome, two guys who have been hounded by doping allegations seemingly forever. Unfortunately, this is the backdrop into which Quintana has been thrust. There is no doubt there is some anti-Colombian sentiment at work here, as the Anlgos have no one compelling to cheer for. They have only themselves to blame for this. Quintana's physical attributes play to his strengths-he is not tall, doesn't weight much, and has an incredible ability to crush it in the mountains. If he could improve his time trialing, or at the very least become good enough in this discipline to avoid losing major portions of time, he'll be one of the all-time greats, much to the chagrin of many who think anyone who rides a bike is on dope, especially if they hail from Colombia. Casting aspersions on riders such as Quintana has become all the rage, and people have made comments over what is going on in South America. But this cat did not come out of nowhere, a la Chris Froome or 2012 Tour winner Bradley Wiggins, with their improbable physiques and their back-dated TUE's for cortisone during competition. If their team is up to no good, they will be found out in due time. Until then, we cannot cast doubt on every rider just because they win. Save that for the putrid Italians, who have a clear history of organized, systemic doping that one can argue is culturally embedded to the point where they can't ride without cheating.

Nairo Quintana's coming out party, Tour de France 2013-